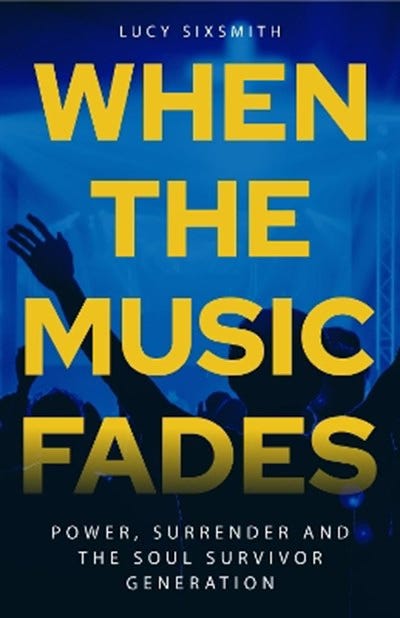

Buy My Sister’s Book!

There’s a point in Martin Amis’s Experience — and I don’t have a copy to hand so forgive my inelegant paraphrasing — where the author recalls his father, the novelist Kingsley, asking him and his brother what they wanted to do when they were adults. Martin reported that he wanted to be a writer while his brother claimed that he wanted to be a painter. “Excellent,” said Kingsley, clapping his hands, “So the Amises will keep their strangehold on fiction while branching out to extend their empire.”

For my sister and me, writing was always our dominant creative passion. We’ve been scribbling ever since we were old enough to clutch pens.

Lucy, being older, led the way. When her teacher asked her class to write a “long” short story, I was inspired to do the same. (“The morning cockerel crowed everlastingly,” was the first sentence and it was all downhill from there.) When she joined a playwriting workshop, she got me in as well despite my being too young for the group. (Years afterwards, Lucy would move to Russia to teach English, which probably did a lot to inspire me to think about moving abroad as well.)

Despite this, we were very different. Lucy grew up to be a diligent student and a passionate evangelical Christian. I hated school even more than I hated church. Lucy wrote elegant and sensitive poems. I ranted online about my ludicrous opinions.

Alas, there is a more of a market for rants about one’s ludicrous opinions than sensitive and elegant poems, so I have somehow become the better known Sixsmith. But while I do my best to write beautiful and lasting work when I have the chance, I rarely read Lucy without thinking, “How did she come up with that?” Her first book — set to be released next year — is a literary triumph.

That’s no surprise to me. What is more of a surprise, perhaps, is that it is also a model of social criticism. It is truly courageous, inasmuch as it attempts to reassess ideas and institutions that meant a lot to its author throughout her upbringing. It is damning but without ever being coarse. It addresses a theme which might be niche — the charismatic Christianity of the nineties and noughties — but makes it wholly accessible and deeply thought-provoking.

I think you should pre-order it. I’m biased, of course, but Martin Amis’s brother would have been biased if he had recommended Money and you should still have read it.