Notes on Weirdness

“Weird” is currently the American liberal-left’s adjective of choice to describe Republicans. I think it started as an attack on JD Vance — Donald Trump’s vice presidential nominee. He was “weird” for caring about fertility rates. He was “weird” for disparaging childless women. He was “weird” for having a bit of a goofy face.

Not being American, I’m not going to debate this charge in the context of the US presidential race. (It seems a bit odd for the party that was energetically engaging in elder abuse to call anyone “weird” but hypocrisy is no political failing.)

Still, it is an interesting charge — a step sideways from “bigot” into more ambiguous but perhaps compelling territory.

I suspect that it appeals to Democrats as the side more popular among women. “Weird” is not just different to “normal”. It can be an unsettling intermediate stage between “safe” and “dangerous”. This matters more to women. But of course it matters to men as well.

A weird thing about being “weird” is that it can be good and it can be bad. Few people want to be called “weird” but fewer want to be called “average” or “conventional”. Being “weird” can mean standing out from the crowd in terms of the freshness and distinction of one’s thought and behaviour. Yet it can also mean standing out from the crowd in terms of their exceptional unattractiveness.

I know this. When I was a teenager, I embraced being “weird”. I thought it made me funny and interesting. At times I was. But the more that I embraced “weirdness” for its own sake, the more I was off-putting and obnoxious. (Then I just became mentally ill and “weird” became inadequate.)

In political and cultural life, it can be good to be weird. Telling the truth as others lie? Weird. Representing virtue? Weird. Breaking new intellectual or aesthetic ground? Weird. Almost everything intellectually, morally and artistically brilliant must have seemed “weird” at some point.

Online, the charge of “weirdness” — the exhortation to “touch grass” and “have a normal one” — can be a coward’s means of denigrating a rival argument without doing the hard work of explaining its untruthfulness or immorality. I may not be able to show that you are wrong or bad. But I can call you “weird” without a single argument. It is a dull, bone-idle way of poisoning the well.

One shouldn’t be ashamed of one’s weirdness. Perhaps my most read piece was a column about evangelical Christians who present themselves as being entirely, tediously mainstream “with a twist of Christianity”. This seems self-defeating. Today, the Christian faith — the idea of God becoming man and dying for our sins — can’t not be weird.

“If someone has a faith worth following,” I wrote:

I feel that their beliefs should make me feel uncomfortable for not doing so. If they share 90 percent of my lifestyle and values, then there is nothing especially inspiring about them. Instead of making me want to become more like them, it looks very much as if they want to become more like me.

Weirdness is not always cause for aversion. It can be cause for aspiration.

Still, we should appreciate — as I so desperately failed to do as a teenager — that intellectual, moral and artistic brilliance seeming “weird” does not mean that it is brilliant because of its weirdness. That genius is so often eccentric does not mean that eccentricity bears essential virtue. Isaac Newton was “weird” but so is the world’s most boring stamp collector.

There is still “good weird” and “bad weird”. Telling hard truths, for example, can be weird in a good way. But context matters. Telling a child that their mum’s cancer is terminal on their birthday, I think we could all accept, is not good weird.

The fact that physical attractiveness tends to gradually decline with age, to take a small but more commonly relevant example, does not mean it isn’t weird — and in a bad sense — to tell random young women that they will “hit the wall”. As much as I’ll defend the right to research unfashionable ideas about biology, meanwhile, holding forth about hereditarianism at a charity fundraiser for abused kittens would be a bad idea. In these examples, it is obvious that transgressing norms is less a symptom of courageous insight than of resentful instability. Where does the weirdness come from? Somewhere inspiring or somewhere unsettling?

Attachment to the concept of being a bold truth teller, moreover, as opposed to attachment to the truth, is liable to entice people into incorrectness. There are few things weirder, and in an unappealing sense, than smug and pompous people who is clearly wrong. This is a special problem in online subcultures because mistruths are liable to be talked up into sacred doctrine. (This is why people should be careful with the term “normies”. There are important differences between being in a community of minds and being in a cult.)

Beyond this, people who are self-conscious in their weirdness are liable to be extremely dull. Many of them are not “weird” at all in the sense of being original or interesting. People my age might remember the time, around the peak of The Mighty Boosh, when teenagers would call themselves “random”. This amounted to nothing more than saying “cheese” at inappropriate moments and wanting to be or sleep with Noel Fielding. It was a dark age.

Weirdness is not something to flee from, then, but nor is it something to embrace. It is, at best, a by-product of courage, innovation or humour — the initial sense of their surprisingness. Without them, it is a bad surprise.

Name calling is for five-year-olds, it's what you do when you either have no actual argument or are intellectually incapable of formulating one. It's too easy in this age of reaction to algorithmically-determined and -generated stimuli to fall into that trap. It makes for little else than bad policy. No one who does that is worthy of a second look, much less support or votes.

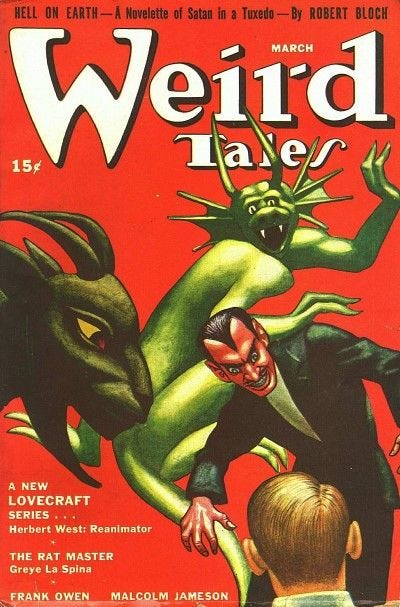

Regarding weirdness and dullness, I'm reminded of self proclaimed witches who, you know, don't actually commune with Satan or commit atrocities, but are just like REALLY into reproductive freedom and against the patriarchy, man. And they just happen to dig the pagan aesthetic. It's just as fake as the so called punk rockers who remind us that racism IS NOT punk. A big part of why everything sucks is because most of what passes as discourse is just moral hectoring