November Diary

Hello,

Obligatory shilling. This month at THE ZONE I wrote about angry mobs, British expats, animals, AI chatbots, engagement farmers, my sister’s book, Upper Silesia and Thanksgiving.

I wrote for The Critic about crime in Britain, Dick Cheney, Zack Polanski, right-wing podcasts, online women-hating, religion and the right, men’s mental health and Medomsley Detention Centre.

Finally, I wrote for Quillette about the state of Britain.

Home front I. Snow arrived in Poland this month. One thing I like about snow is the extent to which it demonstrates the importance of beauty in life. For most of the time, snow is extremely annoying. It’s cold. It’s messy. It’s slippery. It’s dangerous on roads. But one forest walk can make it all worthwhile.

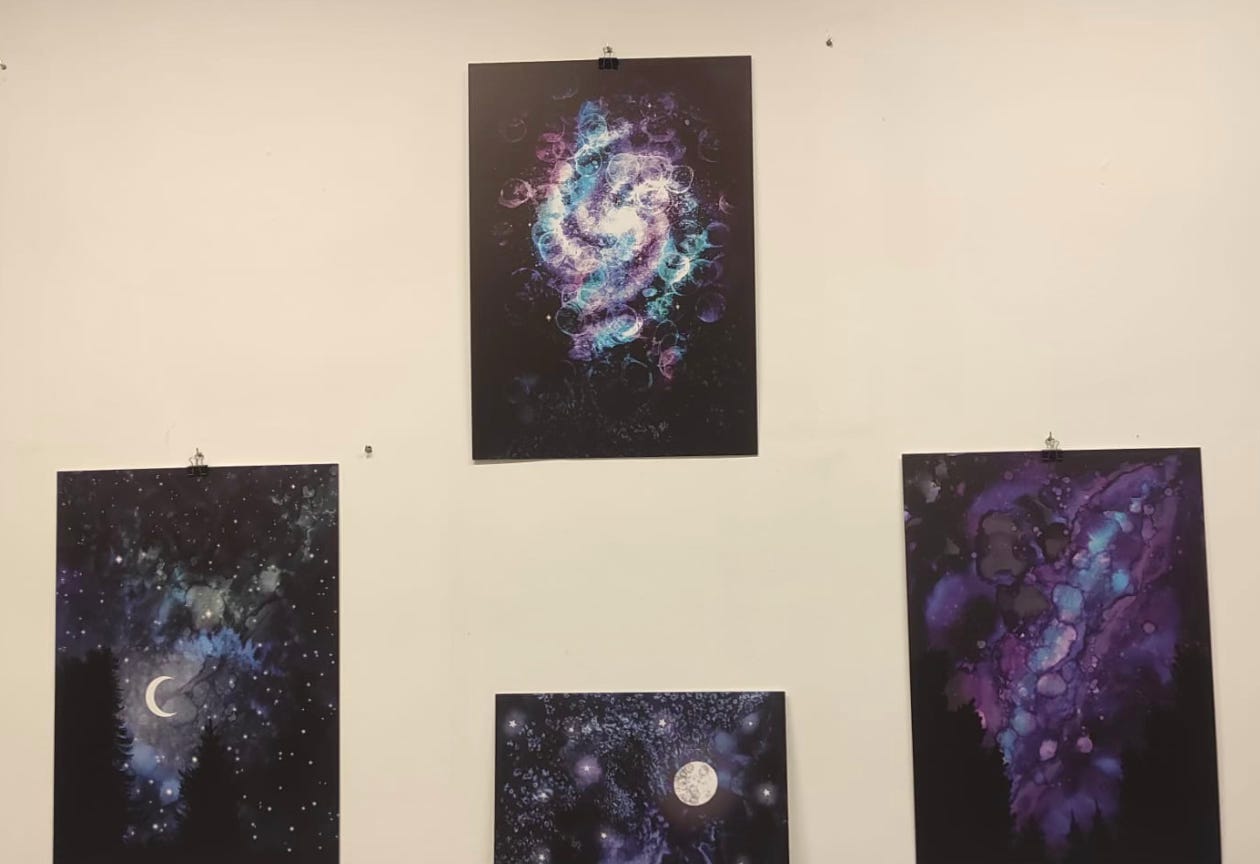

Home front II. It was great to see an exhibition of my fiancée’s illustrations, collecting works reflecting on space and the night sky. I’m so impressed by — and proud of — how she can create visual beauty. I hope that I can sometimes write beautiful prose. But I could no more depict and evoke the beauty of the world around me in visual terms than I could see a rocket and design a prototype for its successor.

Lockdowns revisited. The COVID Inquiry, in the UK, has criticised the British government for not locking down earlier. At The Critic, Max Lacour argues that lockdowns were not inevitable and, indeed, were wrong:

So no, contrary to what the Hallett inquiry’s second report says, a full lockdown was not “inevitable”. Had the scientific advice been better, and had the government had a better understanding of its duty to “preserve life”, then a lockdown might have been dismissed for what it was: an aberration and a bitter attack on what it means to live and die as a human being.

Why Starmerism failed. Ed West explains:

There are different types of failure; a government might immiserate a country, and build problems that can last a generation, yet still be politically successful, ensuring that enough voters are rewarded to win elections. This is successful politics – it’s what braying Right-wingers like me expected from Labour, fearing that they would do enough to bribe and flatter the coalition of the ascendent to ensure electoral success. Luckily, I was too pessimistic, and things are even worse than I expected

The real crisis of literacy. Are we reading too little? No, Kit Wilson argues. We’re reading too much:

Before ditching my iPhone, my days were a nonstop blizzard of words: news, podcasts, YouTube videos, Twitter, WhatsApp, email, Wikipedia, books, magazines. True, even without it, I still spend a decent chunk of my time reading, writing, listening, and thinking “linguistically”. But what made the smartphone particularly pernicious was that it plugged every last gap in the day where I might otherwise have had a brief moment of respite – from words.

Obviously, when Kit says too much he doesn’t mean THE ZONE or the articles to which it links. The editor must have cut out that essential qualification.

The meaning of progress. At The New Atlantis, Charles C. Mann reflects on advances in the modern world:

Condorcet, in other words, was partially right: the advance of science did lead to progress. But the progress was not so much political as material. And it wasn’t so much from science itself as the use of scientific advances — the invention of powerful pumps, the introduction of high-yielding crops, the discovery of electrons, the development of vaccines and antibiotics — to create systems that increased human well-being.

At the same time, Benjamin and Adorno were also partially correct. Condorcet believed that progress was inevitable, even guaranteed by natural forces. Benjamin and Adorno remind us that human failings can always make things worse.

What built Britain? At Aporia, Lipton Matthews argues that British wealth was not built on colonial extraction:

While total factor productivity remained relatively constant until around 1600, it subsequently grew at an average rate of 3 percent a decade until 1760. Crucially, this acceleration occurred before the expansion of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the mid 1600s. It stemmed from improved use of capital, better organization of production, and the shift from agriculture to industry and services.

In defence of cynicism. Chris Bayliss argues that cynicism is a natural response to being treated like an idiot:

Soviet man became used to wobbling his head and having a word with himself. He limited himself to knowing interjections and eye rolls among only the most trusted colleagues and family — or else to dry, oblique humour that was impossible to pin down. An individual may approach particular subjects in a cynical manner, but true cynicism as a way of being is something that a society immerses itself in collectively.

Foma Fomich, pioneer. James Martin Charlton explains how Dostoyevsky explored virtue signalling:

Foma is a character on a par with Shakespeare’s portraits of overweening rogues; he has something of Malvolio’s Puritan scornfulness, Iago’s manipulative genius and Parolles’ bravado and cowardice. He also bears a strong resemblance to Molière’s Tartuffe. Contemporary stages, sitcoms and novels should be full of Foma’s likenesses, mirroring and mocking our encounters with them in reality. But Foma has control of our media and publishing just as he did the colonel’s household. We must on no account allow him to become the fixture Dostoyevsky pictures him becoming in the Stepanchikovo estate. For if we cannot resist this mere popinjay, how will we resist the Demons that Dostoyevsky shows us to be following him?

RIP Tom Stoppard. Alex Larman paid tribute to the great man before his death:

Everyone from Kenneth Tynan to Laurence Olivier saw his innate brilliance and adored him, helping to establish a career that has gone on to define contemporary British drama. Yet if he attempted to begin that same career today, doors would be slammed in his face.

I’m off out into the snow again. Have a lovely month!

Ben

"I hope that I can sometimes write beautiful prose."

You do, you're a competent stylist. :D

I was not aware of Medomsley. Looking through some other reporting, I was noticed this nugget "After Husband’s conviction, [Young, one of Husband's victims in Medomsley] and other victims sued for compensation, and the Home Office fought every allegation. At one point, a doctor was brought forward in court to claim Young was genetically predisposed to being abused."